In the News

Keep up-to-date on the latest news from around the Acts family.

-

![Bridalshow4x3]()

Mystery Donation Inspires Lanier Village Estates' Vintage Wedding Gown Show -

![NFE 100Yopriest 4X3]()

Normandy Farms Estates Celebrates Beloved Resident and Priest as He Turns 100 -

![Dawn4x3]()

Acts Announces New Board Member Dawn Reichard -

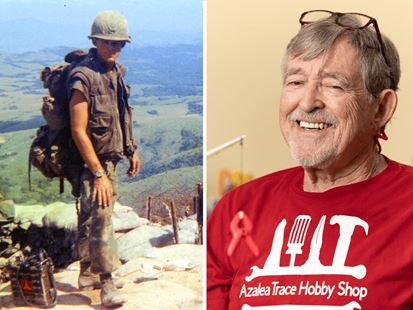

![Atvet Milesdavis4x3]()

Azalea Trace Resident Reflects on Vietnam War, 50 Years Later -

![Alf4x3]()

Acts Legacy Foundation Welcomes New Board Member -

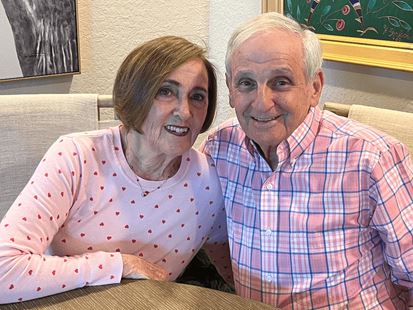

![EBP Fagan4x3]()

Helping Hands and Happy Hearts: Meet the Couple Making a Difference -

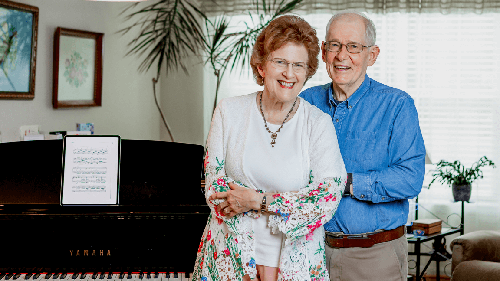

![Lveneighbors4x3]()

A Lifelong Friendship, a Perfect Home at Lanier Village Estates -

![Bradbreeding4x3]()

Future-Proof Your Retirement: Life Care in an Unpredictable Economy -

![Mthuntsville4x3]()

Huntsville, AL Ranked in Top 10 “Best Place to Retire” -

![New Board Member 4X3 (1)]()

Acts Announces New Board Appointment -

![Actsfitch4x3]()

Acts Earns High Marks for Financial Health -

![Bpeeagles4x3]()

Fox 29 Philly Features Brittany Pointe Estates' Eagles Spirit

Media Contacts

Campus Fact Sheets

Select a campus location from the drop-down below

to view and download a fact sheet for that campus.

PDF

Acts Retirement

Azalea Trace

Bayleigh Chase

Brittany Pointe Estates

Buckingham's Choice

Cokesbury Village

Country House

Edgewater at Boca Pointe

Fairhaven

Fort Washington Estates

Granite Farms Estates

Gwynedd Estates

Heron Point of Chestertown

Indian River Estates

Lanier Village Estates

Lima Estates

Magnolia Trace

Manor House

Matthews Glen

Mease Life

Normandy Farms Estates

Park Pointe Village

Southampton Estates

Spring House Estates

St. Andrews Estates

The Evergreens

The Terraces at Bonita Springs

Tryon Estates

Westminster Village